People have many ideas of what it means to be Mexican: the food, the sombreros, the joy, the crime; a wall. While they are not entirely wrong, there is a whole Mexico that is slowly being forgotten and replaced by the misconceptions of today: that of folklore and mysticism. I think that not even the Mexican people remember it clearly anymore. But I know a story about this Mexico: about the sand, the rancheros and the people. It is the story of how Vicente Gutierrez died.

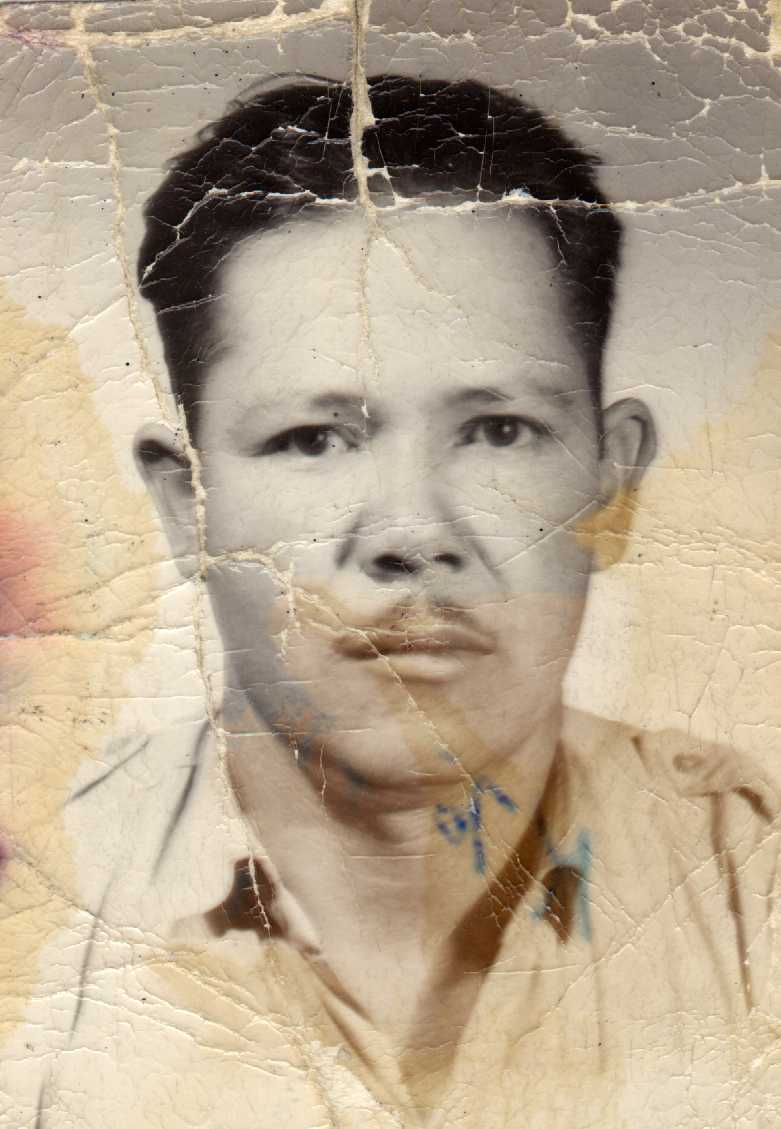

Vicente Gutierrez was a man of Mexico. He had the mustache, the horse, and much like me, he was born into a Mexico that was changing. He was born right after the Revolution. It was a chaotic time. Many men were talking about changes and progress, bringing new ideas from abroad. But Vicente was a simple man. He knew how to work the land, he knew how to shoot, and he drank and sang at parties. If at the time the world was involved in its own melodrama and wars, he knew nothing of this. He was just a simple Mexican man.

Chihuahua is the biggest state in Mexico, and it was blessed with the first railroad in the country. Vicente wanted to work there. Working in the railroad meant you were a man of importance, because who would put an idiot in charge of such an amazing machine?

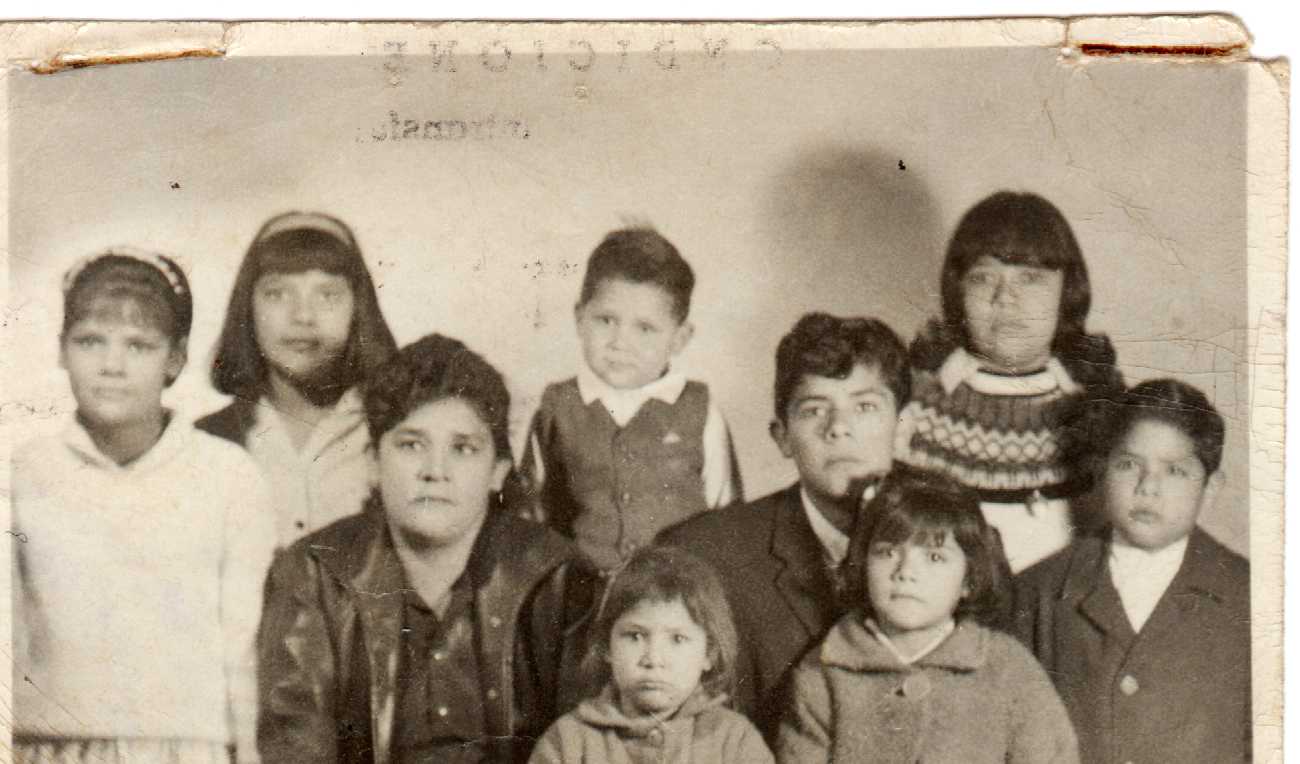

This wasn’t Vicente’s only dream. As in any Mexican tale, there must be drink, tragedy and love. We already know that at least two are happening, but what about love? Vicente met a lovely young woman called Amalia. her dad wasn’t particularly enchanted by Vicente’s macho charm. But Vicente was, if anything, a man that didn’t back down. He did what any good Mexican man would have done for love: he stole his bride. He and his father Camilo, who had ridden with Villa himself, took two horses and spirited Amalia away. They married; however, maybe because of the way he got his bride, maybe because there was the superstition that Camilo was cursed after the war, when they tried to build a family, their first three newborns died. But they were Mexican, strong, hot-blooded Mexicans, so of course they didn’t give up. Andrés was the first one who made it. After that they had eight more children, as you do in rural Mexico. Admittedly, they weren’t very creative with the names. They had three Jesús’s, one José, and three Marías. Running out of inspiration, the last girl they had was honored by having her mother’s name: Amalia.

It was a big family. They lived in a big terrain with fruit trees, chickens and pigs. Like many Mexican houses at the time, it had a Zaguán, which is an entryway before you enter the house. It had a huge cage, full of colorful birds that sang and entertained Doña Amalia. Vicente too had a parrot in the Zaguán. Unlike the other birds, he was free, but he never flew away. He liked to curse and surprise people by talking and making jokes with Vicente. They didn’t have much, but everything they had was self-made.

Eventually Vicente made it, and got a job in the railroad. He sat in the sun and the sand. His job was to help maintain the trains. One day, little Amalia was running in her sandals in a hurry to bring her father lunch, when she accidentally tripped on a rock, her sandals ripped, and the lunch was spilled. Like any child, all she could do was cry. Her father thought it was cute, and just laughed and told his daughter it was fine. They bought some burritos that day.

But this is a tragedy. As good as things were, when Little Amalia was 13, the Catrina, the embodiment of death for Mexicans, decided it was time to come for Vicente. You see, the Catrina is a very beautiful woman, which is so when the time comes, you are not afraid to join her. Even so, some people, no matter what, when death comes are still afraid. Most people don’t see the Catrina coming; she just appears and tells you it is time to go. Vicente, unlike most Mexicans, felt her, saw her coming. It was a normal day like any day. Maybe it was the wind, maybe it really was Camilo’s curse, but he knew it: the Catrina was arriving that day in Chihuahua, and she was going to pick him up.

He was home trying to pretend he didn’t hear her song, but amongst the noise, amongst the birds, amongst the pendejos from the parrot, he heard it. After dinner Doña Amalia was clearing the table, and suddenly Vicente stood up, they looked at each other for a second, and he said:

“I’m dying today”.

Doña Amalia blinked, and like a proper Mexican wife, simply thought her husband was a bit drunk. But Vicente’s eyes were telling a clear story; there was desperation and fear.

“I’m done”, he continued. “I’m dying today. I know it.”

He started walking around the house, as if he were wishing to say goodbye to every corner of the place. Little Amalia woke up and saw them. She didn’t really understand what was going on. You see, even at 13 Amalia didn’t know what death meant. It was part of her culture, but she hadn’t seen it yet. It was indeed a different Mexico. She started following them around the house. Doña Amalia was growing concerned, asking Vicente to calm down or at least give her an explanation of what he meant.

“No no no, I’m done, I love you, hasta luego.” He kissed her forehead and hugged Little Amalia, who still didn’t understand.

Doña Amalia finally stopped him.

“Vicente, relax. Maybe you need some air.”

“No.”

“Why don’t you go the cantina and have a drink, relax?” They looked at each other. He knew that if he left the house, he wasn’t coming back.

“I’ll go.”

He crossed the Zaguán, went across the threshold, and walked away.

Now from this point forward, a lot has been said to be speculation, but the presence of the Catrina was so strong that Vicente’s parrot left as well; a bird that had never flown suddenly knew they were leaving and it was time to spread his wings.

Vicente got to the cantina. He was laughing and smiling, but everyone was saying he was drinking too much, even for Vicente. Around the same time, one of his older sons, one of the Jesús’s, was finishing his work in a construction site. He was also joking and getting ready to go home. He got into a bus and laid his head against the window.

It was closing time. Vicente paid and went outside. The house was closed. This was not his first drunk trip home from the cantina. A friend of Vicente, a taxi driver who had been drinking with him, offered him a free ride home. Vicente knew better, or maybe he was just that drunk. He said:

“Taxis don’t go where I’m going”.

He waved goodbye and started walking. To where? Let’s see.

Jesús was almost home when he sat up, looked outside, and recognized a figure in the dark–his father crossing the street. It was a two-way street. Buses were coming from both directions. Vicente crossed and avoided one, and then he just stopped. Why did he stop? Was it a selfish desire to fulfill the feeling he had been stuck with all day? Or did he see the Catrina telling him to stop running, and just accept her presence? Who knows, but Jesús saw it–the second bus, running over his father and his body hitting the sidewalk. In desperation, he begged the driver to stop, but he wouldn’t, because it wasn’t a bus stop. So, he did what any rational person would do when they see their father being run over by a bus: he jumped from the window of the moving bus. He broke a leg in the fall, but he was there. Vicente’s head hit the sidewalk and broke his skull.

Jesús got to him. Vicente saw his son, and slowly said:

“Told ya”. And fell asleep.

He made good on his promise, and died that day. Jesús was the one who ran home and told Doña Amalia, who was sitting at the table waiting. She wanted to be surprised but at the same time, she wasn’t. Little Amalia heard again the word “death”. She still didn’t understand the word well. All she knew was that her dad wasn’t coming home. A week went by, and as the family tried to heal, the parrot appeared. He was death, in the backyard. He had gone away with Vicente, so maybe he had heard the song too.

What sense can be made of the death of a man who, simply put, wanted to die? That this bizarre occurrence led to me being born? The family left Chihuahua with the hope of achieving the American Dream. Eventually Little Amalia grew up and married across the border, where she had two kids, a boy and then a girl. Life and death create weird paths; death is something that Mexican people, whether they know it or not, grow up with. And whether the Catrina came for him or not, because he heard her calling I was able to exist.

My name is Melina Mendoza Gutierrez. I was born the 19th of February of 1992 in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico. I have always loved writing and learning, I left home two years ago to come to the Netherlands and pursue my dream of being a writer and a philosopher. As a writer I hope to share stories, but more than that create worlds and new ideas to share with others. As a philosopher, I just want to have fun.

My name is Melina Mendoza Gutierrez. I was born the 19th of February of 1992 in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico. I have always loved writing and learning, I left home two years ago to come to the Netherlands and pursue my dream of being a writer and a philosopher. As a writer I hope to share stories, but more than that create worlds and new ideas to share with others. As a philosopher, I just want to have fun.